Did you bring a yellow umbrella?

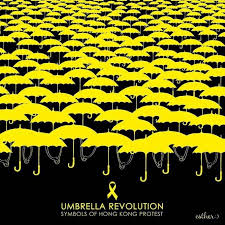

Since 2014, the yellow umbrella has become an important symbol of Hong Kong. This humble and friendly daily item has become the lasting symbol for democracy in Hong Kong.

This umbrella movement that emerged from the mass occupation of September to December 2014 galvanized Hong Kong society, raising the political awareness of many and spurring greater attention on the issue of “future of Hong Kong”.

Why umbrellas? The umbrellas were actually originally used to protect the protesters against the pepper spray used by the police, while yellow colour is the universal emblem of suffrage.

Apart from the yellow umbrella, a visitor to the city can show his or her credentials by knowing 2 very important numbers: the first is 928, and the second is 689.

The mass occupation on the streets started on 28th September 2014 (thus 928). At the time, most citizens were unsure how many days the young people will stay and most thought it would only be a few days. In reality, it lasted more than 2 months. Most citizens’ daily lives were affected by the blocked roads, and traffic jams stretched for miles on Hong Kong Island and across Victoria Harbour, but most adapted. Many opted to either use the MTR (which became even more crowded than usual) or walk instead of driving. Many citizens commented how the air quality in all three of the occupied areas markedly improved. Students, prominent in the movement, also adapted creatively, resourcefully and in an environmental friendly way: for example, inside the Umbrella Village itself, there was a “study area” for the many students, and there were tents-for-rent for those who have full-time jobs and cannot stay permanently.

689 is an intriguing one. It is the number of votes secured by the highly unpopular Chief Executive, Leung Chun Ying (or “CY”), in the “small-circle” Beijing-friendly Election Committee when he was elected in 2012 (the committee had 1,200 seats, thus he received 57% of the votes). 689 has emerged as a pejorative nickname for Leung used by the pro-democracy student leaders and their sympathisers.

But how did the umbrella movement start? Well, it started fairly innocuously, as a week-long boycott of university and high-school classes. This was escalated on 26 September when throngs of students occupied Civic Square, which houses the city’s central government buildings. It was the arrest of Joshua Wong, one of the student leaders who was later named Times magazine’s person of the year of 2014, that triggered the mass civil disobedience that took the form of sit-in protests across 3 key sites and blocking both east-west arterial routes in the Admiralty area. The Occupy Central with Love and Peace group, which was originally planning to start their protests on 1 October, decided to join the mass student protests. Further, the use of tear gas by the police on the protectors soon after it started both triggered sympathy and support of the Hong Kong citizenry and swelled the rank of citizens who joined the movement.

It was all quite a spontaneous movement with no leader. Time magazine described the organized chaos as “classical political anarchism: a self-organising community that has no leader”. Totally surprisingly to the Hong Kongers, the sit-in movement continued for more than 2 months, and to everyone’s relief, it all went relatively peacefully.

The area that was blocked off in Admiralty came to be called “Umbrella square” and had almost 2,000 tents. Camps are referred to as villages and new totally Cantonese-based word-plays are uniting the protestors – for example, Cantonese speakers have created the expression “gau wu” (a pun on “gou wu”, the Mandarin for “shopping”) to express a protest against the disruption created by the arrival of many tourists from the mainland. At the main Admiralty protest camp, toy wolves point to a play on the leader’s surname which in Cantonese sounds a like “wolf”.

What is very clear from the street occupations is the discontent of the young people in Hong Kong as well as their willingness to take a stand. As Anson Chan, the former “iron lady” of Hong Kong, remarked, “You can’t treat the young people in Hong Kong as if their minds are a blank sheet of paper on which you can write at will … The young people through this Umbrella Revolution have demonstrated that they have a mind of their own. Furthermore, they are no longer politically apathetic. They’re prepared to stand up and be counted.”

Christopher Lau, a member of the pro-democracy People Power party, highlighted the significance of the movement: “It matters – although the movement is not successful because the government didn’t yield to any of our requests.” Its importance was to show that Hong Kong could do more: “All these protests that you guys find normal in the States or Europe or France, Hong Kong people detested it. They thought, We cannot have this kind of chaos in Hong Kong, we are an economic city”.

The umbrella movement has also blossomed into a vibrant exhibition of the artistry and inventiveness of the citizens. In the midst of the political and civil strife, the umbrella has become the inspiration for a creative outpouring too.

In Umbrella Square – the area that was blocked in Admiralty – there is the origami mobile of umbrellas, the umbrella army, the patchwork canopy, as well as the umbrella man, amongst others. Everywhere one can find makeshift message boards. The “Lennon Wall” is a stretch of curved staircase in the Central Government Complex that has been covered in thousands and thousands of colourful handwritten Post-it notes bearing drawings, pleas and comments. Reflecting a collective spirit, it is organic and practical, and it just keeps growing.

An art collective calling itself “Stand by You” developed an “Add Oil machine” (preserved digitally) that projects messages of support to protesters onto the side of a building: “add oil” is a popular term of encouragement in Chinese meaning ”keep it up”. More than 30,000 messages were received by the project from 70 countries.

The “umbrella roundabout” installation outside the Legco Council symbolizes the need to reflect on the path of society’s development.

And then there’s the banner that was put across Lion Rock that read “I want true universal suffrage” (in Chinese), which had to be removed the following day by fire services aided by a helicopter. Within days, similar banners were seen on top of Tai Mo Shan and Fei Ngo Shan.

A local artist, Kacey Wong, commented: “This is a kind of bottom-up art explosion, entirely not curated, but still all working on a common theme, as if someone had curated it”. He continued: “If you look at a lot of these artworks, they are no different than contemporary art practice: they convey a message, often through metaphors, rather than being too direct.” Another local artist, Isaac Leung, commented: “It is really touching on the idea of public-ness, where art is being utilized as a tool to express certain things in the public arena.”

Solidarity protests also sprouted up in many cities around the world. Perhaps memorably, at the East Asian Cup qualifying match between Taipei and Hong Kong, held in Taipei, there was a row of yellow umbrellas holding up lyrics from the well-known Hong Kong band Beyond’s hit song, Glorious Years from the 1990s: “Hold on tight to freedom in the wind and rain. We have the confidence to change the future”, and then, as the Chinese national anthem was being played, local spectators joined visiting fans in singing a rendition of Beyond’s other 1990s hit, Boundless Sea and Sky, the unofficial theme song of the umbrella movement.

A newspaper called 28th September “the day Hong Kong cried” and quoted lyrics from Boundless Sea and Sky:

Forgive me for being a passionate freedom-lover all my life,

Even though I fear falling hard some day.

Abandon the ideal — anyone can do that,

But I’d fear the day when there’s only you and I left.

The sea of lights as protesters hold up their mobile phones while singing this song was a sight to behold and deeply moving coming from this ultra-capitalist city. Equally, the Cantonese version of “Do you hear the people sing”, the other theme song of the movement, translated by a journalist who works for the Telegraph, are words to behold:

May I ask who hasn’t spoken out?

We should all carry the responsibility to defend our city

We have inborn rights and our own mind to make decisions

Who wants to succumb to misfortune and keep their mouth shut?

May I ask who can’t wake up?

Listen to the humming of freedom

Arouse the conscience which shall not be betrayed again

Why is our dream still a dream? Just waiting is an illusion

What does black and white, right and wrong, true and false here testify?

For the future of the society, we need to sharpen our eyes in time

May I ask who hasn’t spoken out?

We should all carry the responsibility to defend our city

We have inborn rights and our own mind to make decisions

Who wants to succumb to misfortune and keep their mouth shut?

May I ask who can’t wake up?

Listen to the humming of freedom

Arouse the conscience which shall not be betrayed again

No one has the right to keep silent while watching thousands of candle lights twinkling

Hand in hand, we fight hard for the right to vote for our future

Since we are humans, we have responsibility and the freedom to decide our future

May I ask who hasn’t spoken out?

We should all carry the responsibility to defend our city

We have inborn rights and our own mind to make decisions

Who wants to succumb to misfortune and keep their mouth shut?

May I ask who can’t wake up?

Listen to the humming of freedom

Arouse the conscience which shall not be betrayed again by the government

A local professor, Oscar Ho, put it thus: “What’s happening now with this Umbrella Movement is that you start to see among the younger people a collective obsession with Hong Kong, a Hong Kong identity, which is very unusual for Hong Kong. In the past, when they see something troubling, their first reaction would be emigration. But this is something new. We say, ‘We stay here, we fight’.”

Doing a tour of yellow umbrellas is a must. Start at Umbrella Square. Talk to locals. Learn the vernacular. Breathe in the spirit. Catch the moment.

Smell the air of change.